Exclusive: Why concrete is ‘the only way’ for European floating wind right now

Energy Disrupter

In an exclusive interview, BW Ideol chief executive Paul de la Guérivière told Windpower Monthly that reforming the supply chain will be critical to meet existing targets for fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind energy in the coming years.

“The key driver for cost reduction now, and to deliver for capacity, is really to secure the supply chain, to optimise the supply chain, and to ensure that it can meet the demand and deliver the volumes that are needed,” de la Guérivière said.

“This is typically why [BW Ideol] decided some years ago to invest in the port of Ardersier [in Scotland]. It’s why we consider that you have to invest in production lines that are going to be in position to deliver floaters for multiple projects,” he added.

BW Ideol is based in France and has focused exclusively on floating offshore wind. The company has a multi-gigawatt pipeline of projects and several scaled prototypes already operational, including a 2MW project off the coast of Brittany in France and a 3MW prototype off Kitakyushu, Japan.

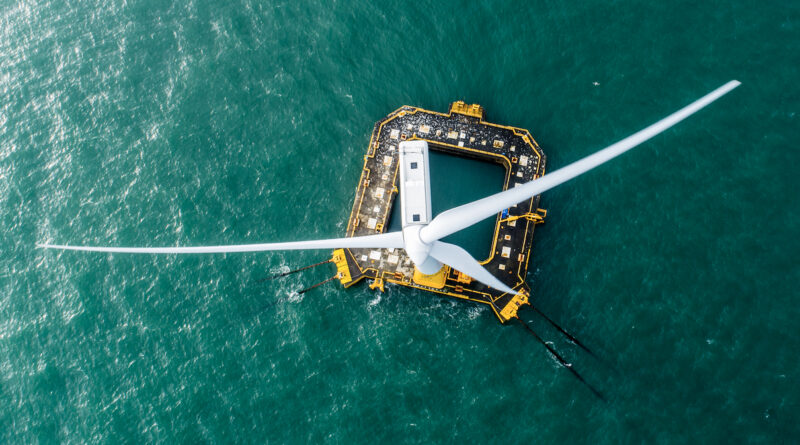

Both pilot projects came online in 2018, and employ BW Ideol’s unique floating barge model, which mounts an offshore wind turbine on a floating concrete and steel barge platform at water depths starting at 30 metres.

BW Ideol’s ‘damping pool’ floating offshore wind platform at its 2MW Floatgen pilot project (pic credit: BW Ideol/V. Joncheray)

The company claims that this design is tailored for efficient quayside installation, improved stability and reduced manufacturing costs. Its use of concrete and steel meanwhile highlights the growing need for a secure supply of both materials in Europe’s wind industry, with the material also in demand for some onshore wind turbine models.

China accounts for more than half of the global production of both cement and steel according to Reuters, with the rest of the world, including Europe, lagging far behind.

With disruptions to the global supply chain continuing to affect offshore wind in particular, de la Guérivière expanded on the importance of returning manufacturing to Europe in order to roll out offshore wind production at the necessary scale and pace.

“We are totally convinced that the only way to deliver a 1GW [floating wind] project in Europe is to have a concrete floater, because there is no way you can manufacture 1GW of steel semi-submersible floater in Asia with a final assembly in Europe, and deliver that in less than three years. There is no way you can do it,” de la Guérivière said.

He added: “The only way to do that, to deliver a 1GW [floating wind project] in three years, is really to have a production line in concrete in Europe…If you want to manufacture steel floaters in Asia for the next three to four years, for example, it would be extremely difficult to find slots in yards that are fully booked in manufacturing, for example, energy tankers. With concrete manufacturing, you are totally independent from this subject. So you have less volatility, less risk, you are under control.”

Delisting decision

Inflation and rising interest rates are threatening the rapid rollout of offshore wind. In order to raise capital in this environment, the company decided to delist itself and become a private company at the end of 2023.

This will help ensure finance for its ambitions to roll out commercial-scale floating wind projects as soon as possible, de la Guérivière explained.

“Most investors have been rushing to focus more on short-term return on companies with positive cash flow and distributing dividends…that’s clearly not the type of company that we are,” he said.

Delisting, de la Guérivière added, “was needed in order to facilitate the process of additional fundraising as a private company, and we consider that it would be more efficient as a private company in the current market condition, and looking at the type of company and the investment profile that we are.”

As countries around the world explore transitioning to renewable energy sources, floating wind presents a key option for locations with deep coastal waters, such as Japan or Portugal, where normal fixed-bottom foundations for offshore wind projects are not suitable.

Europe alone could host an estimated 10GW of floating wind energy by 2030 if governments provide appropriate support, according to industry body WindEurope. But what might that support involve?

“What we need is really to accelerate the consenting. It’s the same issue with fixed-bottom foundations. It’s clearly taking too much time to get final consent and have the project going into construction. It means that, as a developer, you are exposed to long-term risk,” de la Guérivière said.