Right Covid-19 response can set course to net-zero

Energy Disrupter

How governments respond to the coronavirus pandemic will determine whether the global pandemic ultimately helps or hinders efforts to limit global warming and ensure a just transition to clean energy, according to according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

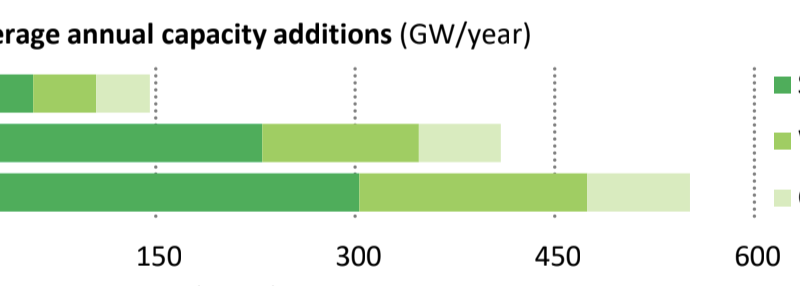

Massive growth in renewable energy capacity – especially wind and solar; increased power system flexibility,; and enhanced efforts to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors such as long-distance transport and heating will be needed to limit global warming.

Tackling all of these challenges will require a vast rollout of well-designed energy policies, according to the IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook report, the IEA offers four divergent pathways for how the coronavirus might continue to impact the world and how governments might respond to tackling it.

Diverging pathways

The report’s two scenarios that retain current policy settings – the “stated policies” and “delayed recovery” scenarios – produce a rebound in emissions as the pandemic eases, albeit a slower one than seen following the 2008-09 financial crisis.

In the stated policies scenario, wind generation expands by more than 60% between 2030 and 2040, while solar PV doubles, but by 2040 wind and solar each still account for only 3% of total primary energy demand – both up from less than 2% in 2030.

Hydropower would remain the largest source of renewable energy, followed by solar PV, and onshore and offshore wind.

However, two other scenarios with more ambitious policies outline how sustainability energy objectives can be met.

The IEA’s “sustainable development” scenario includes a surge in clean energy policies and investment, while in its “net-zero emissions by 2050” case, all countries and companies targeting net-zero emissions meet their goals and put global emissions on track for net-zero by 2070.

Under the sustainable development scenario, wind and solar PV’s combined share of generation rises from 8% in 2019 to almost 30% in 2030, creating a need for robust and well-functioning electricity networks.

Evolution of selected technologies in the sustainable development scenario (SDS) and net-zero emissions by 2050 case

Integrating this level of variable renewable energy depends on adequate investment in all parts of the system, including electricity networks, the IEA noted.

Under this pathway, global electricity demand increases by nearly 20% between 2019 and 2030, and the share of electricity in final energy consumption rises from 19% in 2019 to 24% in 2030.

Meanwhile, the share of renewables in global electricity generation grows from just over 25% in 2019 to more than 50% by 2030.

This growth is uneven, however.

In advanced economies, generation from wind and solar PV more than triples from 2019 to account for one third of total generation in 2030. In emerging markets and developing economies, generation from wind and solar PV increases sixfold, accounting for around a quarter of total generation in 2030.

Overcoming obstacles

The IEA notes several key challenges to be faced as renewable energy capacity and generation increases, including integrating the increased levels of renewable energy and sourcing enough raw materials to produce enough wind turbines and solar panels.

The extent of the rising need for flexibility depends on a large number of factors, the IEA stated.

These include:

- the extent to which wind and solar PV can be deployed in a system-friendly manner;

- the availability of grid capacity;

- existing network congestion points;

- the profile of electricity demand, seasonal weather patterns;

- the balance of wind and solar PV already in the mix; and

- the ability of system operators to accurately forecast and control wind and solar PV.

Policymakers will need to consider all of these when designing a suitably decarbonised energy system, the IEA notes.

Ensuring that clean energy technologies can rely on sufficient supplies of critical minerals will be another significant engineering challenge, according to the IEA.

The increased deployment of renewable energy will lead to increased demand and possibly strained supply of minerals such as lithium, cobalt and nickel in batteries and rare earth elements such as neodymium in wind turbines and electric vehicles.

This could also cause greater political hazards as these materials are often highly concentrated in a small number of countries.

Just transition

Recovery packages amid the coronavirus pandemic give governments an opportunity to enact measures to bring about these changes.

The IEA expects the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent reduced economic activity to prompt a 5% reduction in global energy demand this year, as well as a 7% reduction in energy-related CO2 emissions.

However, the agency’s executive director, Fatih Birol, warned that “the somewhat lower emissions come for all the wrong reasons and at huge economic and social costs”, and that the world instead needs structural changes in the ways we produce and consume energy.

Birol explained: “The economic downturn has temporarily suppressed emissions, but low economic growth is not a low-emissions strategy – it is a strategy that would only serve to further impoverish the world’s most vulnerable populations.”

He added that a “step-change” in clean energy investment offers a way to boost economic growth, create jobs and reduce emissions, but noted that this approach has not yet featured prominently in plans proposed to date, except in the EU, the UK, Canada, Korea, New Zealand and a handful of other countries.