European wind power faces ‘fight’ over scarce metals

Energy Disrupter

European decarbonisation goals will require 35 times more lithium while also boosting demand for other metals, including rare earths, aluminium, nickel, silicon, copper and cobalt, according to a study from Belgian university KU Leuven.

Wind power expansion plans will demand growing amounts of these metals, clashing with rising demand from electric vehicles and batteries, solar and hydrogen energy technologies and the grid infrastructure.

Up to 75% of Europe’s demand for clean energy metals could be met through local recycling by 2050, if Europe invests heavily now and fixes bottlenecks, says KU Leuven’s Metals for Clean Energy study, commissioned by Eurometaux, Europe’s association of metal producers. But Europe faces critical shortfalls in the next 15 years, it warns.

Growing demand

According to the study, by 2050, Europe’s clean-energy technologies will require annually:

-

4.5 million tonnes of aluminium (up 33% on today’s use)

-

1.5 million tonnes of copper (up 35%)

-

800,000 tonnes of lithium (up 3,500%)

-

400,000 tonnes of nickel (up 100%)

-

300,000 tonnes of zinc (up 10-15%)

-

200,000 tonnes of silicon (up 45%)

-

60,000 tonnes of cobalt (up 330%)

The energy transition will also require 3,000 tonnes of the rare earth metals neodymium, dysprosium and praseodymium (up 700-2,600%) — all of which are used in wind turbines.

“Although the EU has committed to accelerate its energy transition and produce a great deal of its clean energy technologies domestically, it remains import dependent for much of the metal needed” the study says. “And there is growing concern about the security of supply.”

Supply risks

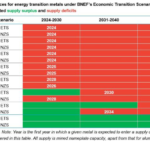

The study anticipates Europe facing supply problems around 2030 for five metals, especially lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earths and copper.

It expects EU primary metals demand to peak around 2040, and increased recycling to help the bloc towards greater self-sufficiency in the following decade, assuming major investments are made in recycling infrastructure and legislative bottlenecks are addressed.

Metals including copper, aluminium, zinc and rare earths are used in wind turbines. Permanent magnet generators, widely used in wind turbines, rely on rare earth metals and are imported mainly from China, which has an almost global monopoly on production.

The European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA) last year finalised an investment pipeline for supplying 20% of Europe’s rare earth elements magnet needs by 2030.

The study also assumes that rare earth intensities in wind turbines can be reduced by 50% for dysprosium, neodymium and praseodymium.

Turbine manufacturers have been exploring options to reduce their reliance on permanent magnet generators.

Local challenge

The study says there is theoretical potential for new domestic mines to cover between 5% and 55% of Europe’s 2030 needs, with largest project pipelines for lithium and rare earths. But most announced projects are struggling with local community opposition and permitting challenges, or relying on untested processes.

Europe would need to open new refineries to transform mined ores and secondary raw materials into metals or chemicals, but rising power prices have already caused the temporary closure of nearly half the continent’s existing refining capacity for aluminium and zinc.

Recycling opportunity

The study finds that, by 2050, locally recycled metals could feed the production of most Europe-made battery cathodes, ERMA plans for permanent magnets production, as well as significant volumes of aluminium and copper.

The EU, however, “must act strongly now to raise recycling rates, invest in the necessary infrastructure, and overcome key economic bottlenecks”.

The large magnets in wind turbines are considered to have good recycling potential. In this study, recycling rates of 90% are assumed across rare earth elements.

Recycling “will not provide a viable EU supply source to Europe’s electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy technologies until after 2040, however,” the study clarifies. “These applications and their metals are only just being put on the market and will not be available for recycling for the next 10-15 years.”