Interview – GEL’s approach to funding and social acceptance for UK geothermal

Energy Disrupter

In this interview, Ryan Law of Geothermal Engineering Ltd. describes how GEL has managed to successfully fund and develop geothermal projects in the UK.

Founded in 2008, Geothermal Engineering Ltd. (GEL) has been leading the way for geothermal development in the UK. The company is responsible for building the United Downs Deep Geothermal Power (UDDGP) project, the UK’s first deep geothermal power plant. Back in 2021, steam was first produced from the production well of the project which was drilled to a depth of 5275 meters.

More recently, GEL was in the news for being awarded £22 million in funding from the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) of the UK for a planned geothermal heating project at Langarth Garden Village near Truro in Cornwall.

To talk about the company’s accomplishments, we sat down with Dr. Ryan Law, Founder and CEO of GEL. In this interview, we discuss the strategy of GEL in securing funding for projects, how GEL approaches community engagement, and which technology can be a game-changer for the geothermal industry.

Congratulations on securing new funding for the geothermal heating project in Langarth. Can you tell us more about this new community and how geothermal heating plays a role in how the community is designed and built?

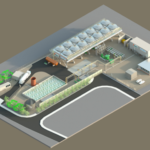

The Langarth project is a good story not just for us, but also for district heating in the UK. This is a good example of a project that has an existing anchor load, which is a big hospital, as well as a build-out of 3500 homes.

Although the UK has been a bit slow on this, overall, we are seeing more emphasis on district heating being built as part of key infrastructure for new developments within Europe. There is now changing legislation in the UK with regards to the building of new houses and what sources of heating can be used for those houses. Before, and certainly within the UK, the alternative was always gas-fired heating. That’s now no longer the case because of carbon reduction targets.

Therefore, developers have to think about other sources of energy – obviously, renewable energy – and that then comes down to a choice based on economics and based on the carbon footprint of the source of energy. It makes sense for most of big developments, such as in Langarth, to install a heat network. Over time, such heat networks can potentially use different sources of energy.

The low carbon heat supply for the housing estate will come from deep geothermal energy. The plant that we are building at United Downs will extract fluids at about 180 degrees Celsius as a primary source. There will be plenty of extra energy post-power production to use for a heat network. When you look at the numbers – and it always comes down to the numbers – in this case, deep geothermal is by far the lowest carbon source, has the lowest costs of delivery of heat, and offers a security of heat as a tariff over a long period of time.

I think what happened in Ukraine also focused people’s minds on long term energy prices and how that can potentially be upset by global events. So, it’s a combination of factors have led to this particular application in United Downs but I’m sure will lead to many other geothermal district heating networks within the UK. We’re a bit a bit behind what’s been happening in Germany, but Germany, again, is pushing for more targets. It seems logical for us to finally catch up.

In the past few years, GEL has been quite productive in securing funding and planning permits for geothermal projects. What can you share about your approach to this development and how you have been able to achieve these remarkable milestones in quick succession?

On the permitting side, we have done a great deal of work over the past five years on education, and community liaison. We have a very good dedicated officer that leads on that and has developed good relationships with the community, with local politicians, and with national government.

I think the permitting has been built on a degree of trust and a degree of education. That’s not to say that it’s ever easy. It’s not easy to find ideal sites as there never is one. But I think that knowledge gained in the last five years has helped in terms of achieving permitting, and we hope to add more and more sites to the list.

Knowledge also plays a role on the funding side. The people in the industry who know me also know that we really struggled to raise money in the early days. To be honest, it’s just experience and momentum that helped to eventually start to get funding over the line. I think we’re also helped, again, by changes in national policy. So, I do think the push to renewable electricity, and the push to renewable heat is now helping compared to where we were maybe a decade ago, or so.

Still, geothermal funding is never easy. I think the amount of experience we’ve had over the last decade of raising money has helped us to understand what sort of approach we need for different types of funders.

Community acceptance and engagement has been a pressing issue for geothermal projects in many parts of Europe, US, and in Asia. What strategies have you employed in securing community acceptance?

Community acceptance is always an important topic. I think one of the key aspects to that is actually understanding who your community is. We do see a lot of endless presentations and research on community engagement, but the real thing is to get out and meet your community. It will be different for every site.

We engage with communities that potentially live nearby our projects, as well as with non-government organizations. We do a lot of work within schools as well. We find that children tend to get pretty excited about what it is we do. I think, younger people in general are very switched on in terms of climate and the potential problems that we have..

I think the combination of finding out who your real community is and constantly trying to meet them, mixed with a big education program, has helped us keep the community on board. You also need to choose your development sites wisely. All of these sites, whether in the UK or anywhere across Europe, they’re always on the shore. So that’s always going to bring up issues. We try to choose sites that that tick a lot of boxes beforehand by making these big geographic information system (GIS) overlays to determine the potential best areas to do our projects in.

That’s an interesting insight. Aside from the technical qualifications of selecting a site with a good geothermal resource, what other factors do you consider?

I think the resource is really only 50% of the picture. We’ve done a very big site selection exercise where we started with about 40 potential sites with suitable resource. But then you start to overlay other factors – connections to the grid, potential heat uses, areas of outstanding natural beauty, the presence of main roads to mobilize a drilling rig – and the number of sites that can be potentially developed shrinks down pretty fast.

We overlay a lot of these factors, and then we can we come down to a smaller number of sites that logistically might be possible. We then do a social engagement search by identifying which areas are very active in terms of objections to any sort of development. We try and avoid those and target areas that are more open to development.

As geologists, we tend to always focus on the resource, but actually 50% of finding the right site is not resource-related.

Funding and community issues aside, what have been the biggest technical challenges developing geothermal in Cornwall?

The well at United Downs is very deep at 5.2 kilometers (It is the deepest well ever drilled on land in the UK). Drilling a well to this depth is challenging, but the drilling technology is there. The difficulty lies in developing a sustainable reservoir with the right flow rates for commercial production, while ensuring that exploiting a permeable reservoir at these depths does not cause induced seismicity levels beyond the tightly controlled permit levels.

From my perspective, drilling technology is relatively established and the temperature at depth is pretty much a given. How we can sustainably and safely develop economic flowrates has always been the challenge. In this case, it’s hitting the balance between aiming for higher flow rate while knowing there is some degree of induced seismic risk associated with that, or accepting a slightly lower flow rate with the assurance there will never be a seismicity problem for the local community.

Right now, we have a handful of companies trying to develop ways to drill geothermal wells faster and cheaper. We also have companies working on closed-loop geothermal. In your opinion, which of these technologies will be the biggest game-changer in the geothermal industry or even just within the Cornish geothermal market?

In the short term, I think the biggest change to the industry will be reductions in drilling costs. That’s more important right now and then heading for the moonshot to “geothermal anywhere” projects. Dropping drilling costs will help the economics for what we do in terms of drilling pretty deep, but in the longer term also help other entities that are trying to drill an entire “radiator” on the ground. For that sort of thing to work economically, we’re going to have to reduce drilling costs a lot. I think that’s the primary thing – let’s get drilling costs down by at least 30%, and things will start to shift.

Aside from power and heat generation, GEL has also been exploring lithium extraction particularly in the United Downs site. What can you say about the potential market for geothermal lithium in Cornwall? Are there any other applications of geothermal resources that you aim to develop?

There is a great deal of interest in direct lithium extraction from geothermal resources. We also have an attractive resource in Cornwall with a high lithium concentration. We don’t have all the answers to this equation quite yet, but we should make some big strides in this area towards actual production probably within the next 18 months.

For a geothermal developer, I think it makes sense to explore that asset, particularly given the expected lithium shortages and the potential carbon footprint of some of the existing lithium extraction methods.

I also think that we’re still at the tip of the iceberg when it comes to mineral extraction from deeper geothermal resources. With the Horizon 2020 consortium, we are looking at other minerals that can potentially be extracted from these fluids. Lithium is the obvious one, because the concentrations are high and the technology is pretty advanced. But I think that there will be other minerals, particularly the rare earths, that will be more important in the next couple of years.

Geothermal resources are traditionally used for power and heat, but there is a whole stack of other things that can be potentially taken out to improve the economics of geothermal. Anyone who has tried to fund geothermal projects has always struggles because of high CAPEX and some utility-scale returns. I think anything we can do to improve that balance will make projects much easier to fund in the future.

For a final word – how do you see the geothermal industry evolving in the next 10 years?

Having been at this for quite a while, I really think that we’re in a great place right now with geothermal. I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a level of interest in funding projects, getting behind projects, and developing both heat and power. The addition of lithium extraction as well has been a very hot topic.

I think that in the next 5 to 10 years, we will see tremendous amount of capital deployed into this industry. Albeit, we will still have permitting problems, as with any renewable energy developer. But I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a level of interest from both government and private investors, so there’s never been a better time for the industry.

This is the sentiment of many players in the geothermal industry right now- that there is an unprecedented level of interest.

Yes, but I think the trick is to turn that interest into money. So, there is a lot of interest, but you have channel that into actual investment.