Malaysia reinvigorating interest in geothermal with 1st Geothermal Conference

Energy Disrupter

The first Malaysia International Geothermal Conference gathered local and international experts aiming to contribute towards Malaysia’s geothermal development.

The Southeast Asia region has earned an excellent reputation in the field of geothermal power generation. As of the end of 2023, the Philippines and Indonesia have a combined installed geothermal power capacity of 4370 MW, or about 27% of the global installed capacity. Taiwan also has operating geothermal power plants in Qingshui and Sihuangziping, and Thailand has had a 300-kW geothermal installation running since the 1980s.

Practically surrounded by these powerhouses, it is perfectly reasonable that Malaysia has shown interest in developing its own geothermal sector. As part of these renewed efforts, Malaysia recently held the first Malaysia International Geothermal Conference (MIGC) in the premises of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia in Selangor.

Organized by Dr. Mohd Hariri Arifin from the Department of Earth Sciences and Environment at UKM, the event highlighted the research and exploration work being done at the geothermal sites in Malaysia, as well as technical insights presented by international speakers. Participants also took part in a workshop and a field trip to some of the potential geothermal sites in Peninsular Malaysia.

Reinvigorating interest for geothermal in Malaysia

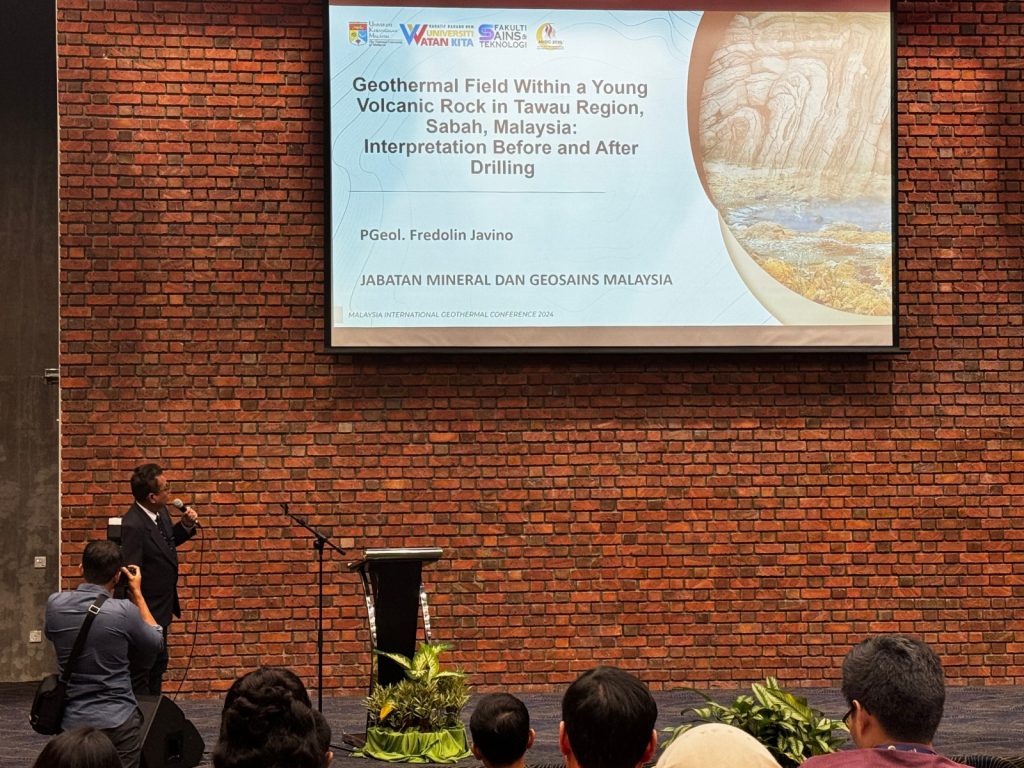

Malaysia had already ventured into geothermal development more than a decade ago, initially identifying the Apas Kiri site in Tawau in Sabah Malaysia as having good geothermal potential. Over the following years, the project received investments and government funding, building towards a commercial operations date by 2017.

Things did not turn out as expected for the Apas Kiri project, with the site seemingly abandoned by late 2018 and the license revoked by Malaysia’s Sustainable Energy Development Authority (SEDA). At the time, government officials stated that there had been no progress in the project since 2016 and that the company had already ceased its operations.

Despite the setback, interest for geothermal development is coming alive again in Malaysia. Earlier this year, a tripartite agreement was signed between UK-based consultancy Primeval Energy, the Institute of Geology Malaysia (IGM), and Digital Geoscience Global Sdn Bhd (DGeG) to conduct thorough assessments of geothermal energy potential in Malaysia.

There is still some interest in the Apas Kiri site, but there has also been a shift in focus to developing non-volcanic hot spring sites in Peninsular Malaysia just north of Kuala Lumpur. Although initial targets are small in scale, the aspiration is to build a first “proof of concept” geothermal facility to help spur more support from the government, the financial sector, and private developers.

“Our goal is to develop any of the promising sites in Malaysia for our first geothermal power plant. It can be small, even just 100 kW. We can start with that, and maybe it can help open the eyes of potential stakeholders,” said Dr. Hariri. “And then we can go for MW scale, or even GW.”

“It is important for us to try. If we don’t try, then we will never know.”

Learnings from neighboring countries

One of the objectives for holding the first MIGC is to invite geothermal experts from other countries to share their knowledge and help empower the local sector. As such, the event’s keynote speakers were Dr. Yunus Daud from the University of Indonesia and Dr. Wipada Ngansom from Ramkhamhaeng University of Thailand.

During his presentation, Dr. Daud discussed the value of geothermal exploration technologies specially applied to the characterization of low to medium-temperature geothermal resources. Surface manifestations in such systems may not be so apparent, so remote sensing systems and geophysical measurements are particularly critical.

Dr. Ngansom also shared some insight on how geothermal sites in Thailand are evaluated and ranked based on a system of positive attitude factors. Aside from technical factors including reservoir size and temperature, positive attitude factors take into account market and infrastructure considerations such as terrain, proximity to market, and distance to power distribution lines. This system provides easy-to-follow guidance on selecting the hot spring sites with the highest potential. It is also a useful tool for communicating with local and national decision makers, as well as potential investors.

The discussions during the keynote presentations were particularly relevant for Malaysia in the context of the Ulu Slim hot spring site. Located just north of Kuala Lumpur, Ulu Slim has been one of the focus areas of geothermal studies done by UKM. Studies indicate that Ulu Slim is a fault-controlled geothermal resource with a radiogenic heat source.

Several other international speakers presented during the MIGC. From scaling mitigation in Dieng in Indonesia to slimhole drilling for geothermal exploration in Singapore, the international experience represented during the event reflected the level of support for Malaysia’s geothermal growth. As Malaysia works for its aspiration of having its first geothermal power plant, collaboration with international experts will undoubtedly be part of its development strategy.

To this end, UKM has been collaborating with Indonesia-based NewQuest Geotechnology to conduct geophysical studies on their areas of interest. Dr. Hariri stresses that there are no local contractors or service providers for magnetotelluric (MT) surveys, making this collaboration instrumental in the progress of geothermal research in the country.

High-potential sites for geothermal in Malaysia

Part of the conference was a field trip to some of the high-potential geothermal sites in Peninsular Malaysia. Located just a few hours north of Kuala Lumpur, the hot spring sites are being used for geothermal research and are eyed for further geothermal development.

The Lojing hot spring site located in the Lojing Highlands is being targeted for the first mini geothermal power plant. A shallow well had already been drilled at the site to a depth of 138 meters, which is now producing hot water at a temperature of around 78 °C. There are plans to drill a deeper well, but a driller with more experience will be needed.

“We drilled to 140 meters, and then the local driller surrendered,” admitted Dr. Hariri. “We cannot go deeper because the pressure is quite high and temperature is increasing. Hopefully, we can be connected with a company with the equipment to support our exploration work and help us prove the presence of this hot reservoir.”

Providing stable electricity to the local community is one of the motivating factors for geothermal development in Lojing. Under current conditions, the locals are dependent on diesel generators for power. “When the diesel runs out, then they are in the dark,” says Dr. Hariri. Introducing geothermal power can also create more opportunities for the area as a tourism and educational hub.

The Ulu Slim hot springs, located around 85 kilometers south of Lojing, is another site of interest. Should the site be developed for geothermal power, it can supply electricity to Malaysia’s national car factory, the so-called “Proton City.” UKM is also working to establish a geothermal learning and research centre at the Ulu Slim site.

Detailed exploration of the Ulu Slim site had already been undertaken by NewQuest Geotechnology with recommendations for further development.

An optimistic view, but support is needed

Groups advocating for geothermal development in Malaysia are highly motivated and passionate, but there is admittedly a lack of in-country skills and technology to fully realize their geothermal aspirations. “Geothermal is still quite new for us and we do not have clear guidelines yet for its development. This is why we keep proposing geothermal projects and educating others about the potential for geothermal,” said Dr. Hariri.

“We are looking for collaborations with those who want to be pioneers for geothermal in Malaysia. We are not good in everything, so we are very open to others with the expertise.”

Dr. Hariri’s group is also working with UKM Pakarunding to establish standards for Environmental and Social Impact Studies related to geothermal development. These are the initial stages in creating a regulatory framework that will make geothermal development in Malaysia more secure and predictable, thus also attracting more investment. Through the help of SEDA and other related parties, the goal is to create a more attractive regulatory environment for geothermal development in Malaysia.

As said in one of the presentations during the conference, addressing the barriers to geothermal electricity and heat development in Malaysia will require concerted efforts among academia, industry, and government agencies. The road ahead remains long for Malaysia, but holding the MIGC has been an important first step.