Dutch 21GW ambition needs policy shift or offshore profits will plummet, report warns

Energy Disrupter

In a new study, the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) mapped out the economic risks relating to this based on two scenarios. One assumes low electrification of industry, while another assumes high electrification.

“In the low-electrification scenario, offshore wind is revealed not to be profitable in 2030 if current policies remain unmodified,” the TNO report said.

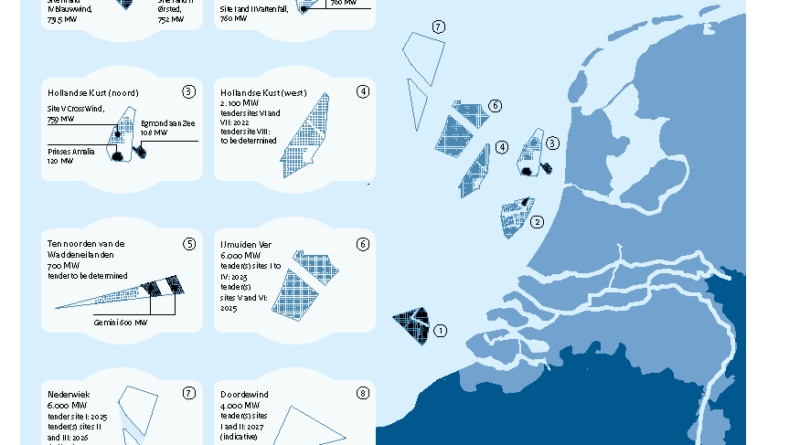

Earlier this year, the Dutch government increased its offshore wind target to 21GW by 2030.

The report warned: “Current market trends, such as the expansion of production capacity for renewable energy, the electrification of industry, rising gas and CO2 prices, and the need for grid reinforcements, are making the electricity market more volatile. Combined with the gradual abolition of subsidies, these trends are increasing the risks for the offshore wind energy sector.”

Low-electrification scenario

The low electrification in 2030 scenario is based on the Netherlands’ Climate and Energy Outlook 2021 and its national Climate Agreement. Here, there is no tangible goal for industrial electrification on the demand side, while on the supply side, there is full deployment of all offshore wind capacity planned.

Under these conditions, the surplus supply in the energy market will result in a 13% curtailment of offshore wind energy production, even after taking export into account, said TNO in its whitepaper: ‘Offshore wind business feasibility in a flexible and electrified Dutch energy market by 2030’. The business case for wind farm operators will only be positive for 30% of the time, it added.

For a feasible business case in the low electrification scenario, the offshore wind sector should look at other types of business models by seeking collaboration with industry, according to the report.

“By combining investments and creating direct agreements regarding the delivery of electricity by means of power purchase agreements (PPAs), the effective yield of such an integrated business model could increase by between 5 and 33%,” the report said. These PPAs should be with a flexible asset, such as an electrolyser or power-to-heat/electric boilers.

High-electrification scenario

In a high-electrification scenario offshore wind becomes profitable and there is virtually no curtailment. Here, all planned offshore wind production capacity is used. The critical difference though is that it is assumed the EU’s ‘Renewable Energy Directive II’ (RED II) and the ‘Fit for 55’ package are in force. These set clear goals for industrial electrification.

“The market price will be financially attractive for the business case 80% of the time,” TNO said. Gas will still be needed sometimes, such as when electricity demand increases but no renewable sources are available, it added.

PPAs still ‘recommended’

“To create an integrated business model that is beneficial to both the offshore wind sector and the industrial end users, a PPA is still recommended in this scenario,” the TNO study noted.

A PPA, it said, can help achieve the country’s CO2 emission reduction targets and reduce the CO2 emissions of the energy sector. “It could also help to buffer against fluctuating electricity prices, reducing strong fluctuations in the electricity market.”

It added: “The direct integration of offshore wind with flexible assets for power-to-heat (P2H) and power-to-hydrogen (P2H2) conversion by means of a PPA improves the offshore wind business.”