[Article] Living Better with Less Energy

Energy Disrupter

At times, the solutions to our problems are hiding in plain sight. Sometimes the hardest part is taking the time to examine things that we assume don’t need to be examined. Consider my friends the Vetters. I’ve known the family for nearly ten years. Zak’s father, Craig Vetter, is an industrial designer and inventor who gave the motorcycle world the modern touring fairing. Craig also has a lifelong passion for doing more with less and experimented with streamlined motorcycles, not only designing them but measuring and learning the effects of streamlining. He found that doubling and even tripling their effective range was easy when the bike was enclosed in a teardrop shape! Craig understands the concepts of efficiency and has passed this knowledge on to Zak, who was preparing to install a large solar array to power their property when our paths crossed. As Zak explained it, though he had grown up seeing efficiency firsthand and how it dramatically improved the range and performance of vehicles, he had not recognized that the same thinking could be applied to houses.

Efficiency Improvements First

While telling me of his plans to power their ranch from the sun, I had the opportunity to propose that before building a big PV array, we look into what efficiency improvements could be made to the buildings. I explained that making the buildings efficient would not only reduce the size of the array needed, but also save roof space, along with the maintenance of whatever array was built. Additionally, having a smaller load gives one more choices in managing power outages or even considering going off-grid. At first skeptical, Zak began working through the suggestions I had for reducing the energy use of the buildings. I had proposed that if he did not change habits, he could save 50%. If he was willing to change habits, he could save 80% with basic efficiency measures, which he later told me he thought was a very tall claim. This is basic stuff for energy folks, but we are competing with big shiny objects! As an example, people think that installing an “instant” water heater will magically give them instant hot water when nothing has been done to improve the distribution system.

We all know that much of what home performance contractors do does not require giant brains, but rather tenacity and a good tolerance for discomfort. (Zak Vetter)

Before building a big PV array, we looked into what efficiency improvements could be made to the buildings. (Zak Vetter)

Do It Yourself

One of the fun things about working with Zak is that he is self-employed and can manage his time as he wishes. Also, he’s technically adept and learns quickly, so is able to perform nearly all of the work involved in making the buildings and infrastructure perform better. We all know that much of what home performance contractors do does not require giant brains, but rather tenacity and a good tolerance for discomfort. Air sealing in tight attic spaces while avoiding roofing nail tips comes to mind. Many of the tasks are tedious and repetitive but not particularly difficult.

A benefit of this for Zak is that he can devote time as he has it, to continue making the property perform better even if it’s just a section of a building at a time. He doesn’t need to hire out much of the work, so saves money and scheduling headaches. Perhaps more significant is that most of the work done on his project was essentially low-skilled labor. As Zak put it, “Just about all the equipment and materials came from Home Depot and Amazon.” Most people could do this if they chose to make the time. (We probably can all find the time, but for some reason we spend it on things that are more fun than crawling around in hot, dusty, itchy attics—like drinking designer coffee and going to the movies.) Additionally, the return on investment is much faster with smaller labor costs. At present, all measures taken are paying for themselves at around 25% per year and will last for decades, while making the property more valuable. In a nutshell, Zak is investing in himself.

Craig Vetter at the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum in July 2016 with the 1981 Streamliner, which features Vetter’s innovative, streamlined teardrop shape design. (Kraig Schultz/Wikipedia)

One of the most effective measures was getting rid of two propane-fired water heaters. They were replaced with a single-tank solar water heater with an electric element in the top of the tank. Here Larry works on installing the solar thermal collectors for the system. (Zak Vetter)

Appliances

I mentioned early on that many of the solutions are right in front of us, and one way Zak learned this was to measure the energy consumption of each of the electrical appliances in the house over a ten-day period. This showed what really used the energy in his household, given his lifestyle. Zak originally felt that he could do a decent job by guessing, based on the age of the appliance and the size of the wire powering it, but was surprised to find out how little these things were related to total consumption. As he measured appliances, he found that energy usage was more closely related to the length of time the appliance ran rather than to how much power it drew instantaneously. Rarely were the nameplate data or Energy Star sticker even a remotely accurate estimate compared to the measured use or dollar cost. Once he had the actual numbers, there was no mystery about what was using the power. It became a simple matter of deciding what to replace and when (see Figure 1).

2014 vs. 2018 Appliance Comparison

Figure 1. There was no mystery around what was using the most energy. (Zak Vetter)

External fridge control. (Zak Vetter)

In the Vetters’ case, one refrigerator and one freezer (both working as designed) were found to be responsible for the bulk of the plug loads, accounting for more power consumption than all of the remaining measured appliances combined. Here again, I had the opportunity to propose some fun solutions. Rather than replacing the units with newer versions of the same upright design, I suggested chest-style units. Their main advantage is that when you open them, virtually none of the cold air falls out of the unit, unlike their vertical counterparts. A leaky seal in a chest-style freezer won’t affect power consumption much either. Yes, modern designs have lots of storage built in, but none of them can compare to a single-chest unit in terms of energy efficiency. Zak took things a step further and found that chest-style refrigerators are not generally sold, but with a mechanical plug-in refrigerator thermostat, he could convert a chest-style freezer into a refrigerator. Also, the nature of this solution allows Zak to simply unplug the thermostat, and the refrigerator becomes a freezer again. Zak did not want to give up refrigerated space for the sake of saving energy. In the end, because the new units used so much less energy, he added a third unit to increase his storage capacity. Think living better on less! Even with the substantial gains from the other appliances replaced, the refrigeration improvements alone save more than 2,000 kWh every year. He also changed out over 500 lights to LEDs, which now give better light and far longer life.

But the improvements to the Vetters’ property have not been limited to electrical appliances; they did all of their cooking and water heating with propane. One of the most effective measures was getting rid of two propane-fired water heaters, one that was installed with a 24-hour recirculation line! They were replaced with a single-tank solar water heater with an electric element in the top of the tank. The recirculating pump was also removed from the plumbing and more than 50 feet of hot-water piping cut out. With these measures, propane use has been cut by 79%. Even with those changes there are major gains still to be made cutting out possibly hundreds of feet of poorly plumbed hot-water line running willy-nilly throughout the houses.

An infrared photo of my cat walking on carpet. (Zak Vetter)

Air Sealing and Insulation

One of the bigger problems has been keeping warm in winter. The Vetters used to go through about four cords of wood each year. Although there is much left to be done, air sealing and insulating have reduced the yearly need for wood down to two cords. Cutting and splitting all that wood is likely a chore Zak won’t miss. All this air-sealing work has been done without the benefit of a blower door, but rather with an infrared camera, the Flir One, which makes it easy to “see” heat leaks, or heat buildup around light fixtures. I’m impressed with the technology.

Plumbing

The Vetters have a gravity-based water supply system, and each of the five buildings served is at a different elevation below the tanks. They also live in a high-fire-risk zone, and there are no municipal hydrants within a mile of the property. They must be their own first line of defense in the event of a wildfire. The water system was built the way anyone would build it, with straight lines of buried pipe, run to the buildings and connected together with right angles . . . sometimes many right angles. Right angles can add a lot of pressure drop to piping systems, more as flow increases. In fact, Gary Klein, another energy zealot, has been measuring just how great the restrictions to flow are and has explained that done poorly, 90s can cut the maximum flow rate in half.

Zak testing water quality in a storage tank. (Zak Vetter)

Now consider the Vetters’ scenario. They have 2-inch main lines connected to 10,000 gallons of elevated, stored water. In some cases the hydrant locations have less than 30 psi static pressure. Even the closest and most direct hydrant on the property was found to have ten 90˚ ells between it and the tank. Whether Zak is running a fire hose himself off the gravity pressure or a fire engine is pulling water from the hydrant, those ten 90s would have been there, restricting the water flow at perhaps the absolute worst time. So as repair work comes up for the water system, Zak has been correcting the plumbing to get better flow. Just between the water tanks and the closest house, Zak has removed more than 50 of those bad 90s, without even touching the pipes inside the houses! Additionally, as new piping is installed, it’s built with sweeps and long bends to maintain as much flow as possible.

Two examples of plumbing improvements. From this . . . to this. (Zak Vetter)

We even took the time to measure the internal diameters of the PVC and brass ball valves used in the plumbing to ensure that the valves were not acting as flow restrictors. Why check the valves? It says 2-inch on it so it must be 2-inch inside all the way through the valve, right? In the case of PVC valves, Zak ended up upsizing them to maintain maximum potential flow (meaning 2 ½-inch PVC valves were installed for 2-inch PVC pipe). Is this overkill? Depends on what problem you’re solving. Certainly the 1-inch lines going into the houses will never experience whatever small restrictions the slightly smaller PVC ball valves create, but for fighting a fire and getting every last bit of water possible, it certainly is reasonable to consider eliminating as much restriction as possible. As Zak pointed out (somewhat annoyed), “It’s practically the same effort to install this wrong as it is to install it right!” I’ll add that Gary Klein has found that installing hot-water systems right actually saves material and time, costing less than doing it inefficiently. A more thoughtful water line installation at the Vetters’ would have saved a load of fittings and given better flow.

Another benefit of reducing the pressure drop in the supply piping is that the booster pump hardly needs to function to get decent flow now, where it used to be really noticeable if the pump didn’t come on. So there are also some energy savings to be had with better water flow.

There have been a few unexpected benefits from doing this work, as you get into places one normally wouldn’t go by choice and see things you hadn’t expected. Here is a fun photo (see below). This was up under eaves behind a lot of vines. You can see the ratty teeth marks. Given enough time, they will get through pretty solid wood. No doubt the house is a bit healthier now without these “guests.” Other benefits of doing this work have been getting to visit and fix plumbing in the attic that, by itself, was more trouble than it was worth to fix. But since we were there working in the space, and presented with the opportunity to fix it, why not do so? This also allowed us to tidy up wiring before it got buried in insulation.

From Gas to Induction Cooking

Another benefit worth mentioning has been in the switch from propane gas cooking to induction. There were concerns that induction cooking would fall short of what gas could do, but it’s been found that induction has at least as good control during cooking, and actually can have greater heat input than gas. It’s also safer in several ways. First, it doesn’t get so hot as to become a burn hazard, and second, it cannot leak propane gas and create an explosion risk

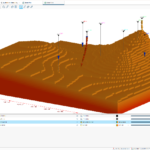

Zak’s place from a bird’s eye–or in this case a drone’s eye—view. (Zak Vetter)

A Win-Win

What can we conclude from all this? First, it’s clear that we can make our homes perform far better in a number of ways without excessive cost if we can find time to do the grunt work ourselves and if we remove the typical contractor think of “get it done to move onto the next job.” It helps to think of every part as interrelated to every other part. (Thank you, Linda Wigington!) So we see how a change here affects something over there. For example, we see how getting better water flow affects power consumption and also safety, while giving better performance. Another possible sales tool for efficiency is that we can actually help people to live more comfortable, healthier, less energy-intensive lives while saving money. Imagine how the money not spent on one asthma-related trip to the ER could be spent to do a lot of building improvement!

On a more granular level, we can look at the decrease in energy consumption from electricity, propane, and wood. Just have a look at Figure 2, which shows the reductions in usage.

Figure 2. We can actually help people live more comfortable, healthier, less energy intensive lives while saving them energy.(Zak Vetter)

We can look at service benefits from the work performed, such as better water flow at fixtures, more evenly heated living spaces, increased food storage space, and better and longer-lasting lighting. Then we have safety improvements, such as more water available for fire protection, healthier air from induction cooking versus gas, and the multiple health benefits of not sharing one’s living space with rats! That’s why we’re aiming to live better on less.

Zak Vetter was raised on the Monterey coast of central California. He has been self-employed teaching and repairing computers for more than 15 years. Zak met Larry in 2008 when Larry fixed one of his water heaters. Since that day Larry has been introducing Zak to the wide-ranging world of home energy efficiency; Zak is now hard at work (stealing) adapting the designs of Larry’s house to his own property.