[Article] Editorial: The Energy Costs of Moisture

Energy Disrupter

Large parts of North America have suffered from unusually rainy and wet conditions during the past year. The costs of flooding and water inundation are well known and they rank third highest among insurance claims. The impact of moisture, such as vapor in the air, liquid and vapor within building materials or condensed on surfaces, is more subtle. People don’t talk about a moisture bill like they do for heating and cooling bills but it exists and it’s large.

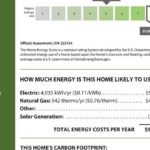

A moisture energy bill is complex because it is dispersed among many devices. If we were to create a moisture energy bill, here are some of its constituents. The dehumidifier is the most obvious contributor to a home’s moisture bill. About one fifth of American homes have dehumidifiers. Operating patterns vary widely but, in Mid-Atlantic states, they can easily run 2,000 hours/year and consume 1,000 kWh/year. That’s almost 10% of an average home’s electricity bill! Dehumidifiers in basements need a sump pump, too; this can add more electricity consumption.

Alan Meier (Yasushi Kato)

Alan Meier (Yasushi Kato)Excessive moisture in homes leads to mildew, mold, increase in dust mites, and other issues that lead to odor and health problems. It also leads to poor comfort and can damage building materials such as rotting wood and peeling paint. Ventilation is a partial solution… and another constituent of the moisture bill. People ventilate for other reasons, such as odor removal, so the couple hundred kilowatt-hours per year associated with bathroom fans can’t be blamed entirely on moisture.

Other elements of a home’s moisture bill are more subtle. For example, many air conditioners do a poor job of dehumidifying. This leads to overcooling in order to achieve satisfactory thermal comfort and a higher cooling bill. Improved dehumidification saves energy like increasing the summer thermostat setting a couple of degrees. These problems are made worse in high-performance homes that have very low thermal loads with a correspondingly small amount of dehumidification from the air conditioner. In many climates a dehumidifier is essential for a high performance home, and this offsets some of the thermal energy savings.

Water damage caused by rainwater leaking through a roof. (Ed!/Wikipedia)

Moisture reduces the effectiveness of insulation. Wet insulation translates to higher heating and cooling bills. The problem may be confined to a single wall or corner, but the costs are nevertheless real.

Put all of these costs together and the moisture bill in many homes will approach the bills for heating or cooling. And this doesn’t include the costs of material damage (or health complaints) from moisture-induced mold, mildew, and dry-rot.

How can a home’s moisture bill be reduced? Each home’s situation is different and there isn’t space here to detail all the options. Installing a more efficient dehumidifier is a reliable first step, but more efficient ventilation fans and controls help, too. On the other hand, a more efficient air conditioner might not help because some manufacturers sacrificed dehumidification efficacy to achieve a high thermal efficiency. A variable-speed unit (even if only 2 speeds) may be more effective. Replacing wet insulation is a much bigger job but might be more easily justified for the health benefits rather than energy savings. When internal sources of moisture are the culprit, targeted solutions, such as enclosing the shower, could be the simplest solution.

Providing thermal comfort and maintaining material integrity in a home is more complicated than just heating and cooling. Creating a moisture bill is one way to highlight its complexity and perhaps raise the profile of drying out a home.